Note to the reader: I originally wrote this in 2009 at the request of the editors of a proposed book called Permaculture Pioneers. It was slated for inclusion, but I withdrew it after the publishing process dragged on. The book was eventually published without this chapter. You can find the book here.

Tim Winton

An Integral Permaculture

I’ve practiced and taught permaculture, at times intensively, for most of the last fifteen years. In that time my perspective on permaculture has changed and evolved, as has permaculture itself. If at times in this article I am critical of elements of permaculture, it is not to be negative or to lessen the importance of the discipline, but to examine the points of pain and disappointment that that have lead me to new understandings and new directions. The same should be true for the movement itself, and I’m writing here with this in mind.

Permaculture was my portal into the world of sustainability and environmentalism. Before I encountered permaculture and the realization that the planet (and humanity with it) was heading for trouble, I lived with a kind of optimism, a sense of acceptance and a general, if ignorant, ease about the world. Permaculture changed all that. I can remember the first time I heard the word, oblivious to the fact that this one little utterance would radically change my view of the world and define my existence for at least the next twenty years. I was tree planting with a crew of mostly fringe dwellers, alternative folks and other students in remote, mountain wilderness in Western Canada. Simon, a soft spoken fellow with long hair and an eagle feather held in place with a thin leather headband, introduced me to the fateful word. We sat on a log eating lunch out of dusty rucksacks. I told him about my impending trip to see my father in Australia. He told me I should look into a Tasmanian called Bill Mollison who taught a way of sustainable living called ‘permaculture’. He explained the Willing Workers on Organic Farms (WWOOF) network- living by volunteering on other people’s organic farms for food and board, and his encounters with permaculture in the Pacific North-West. At that point I don’t think I really understood what permaculture was, but it settled in the back of my mind as an environmental curiosity, a talisman as exotic as the fellow who introduced me to it.

I realize now with reflection, that the story of my experience in permaculture is essentially my journey through that environmental portal to a world of somewhat painful awakening and increasing sensitivity to the environmental and social disaster humanity was perpetrating. After that, I undertook a long, determined and often difficult attempt to make permaculture work as a method of sustainable living. Finally, there was a gradual spiralling back around to a renewed acceptance and appreciation for the society I was born to, our time in history and the wide world with all its foibles and wonders, ugliness and beauty, sustainability and unsustainability.

From Sensitivity to Integration

I’m telling the story here, because I think this renewed acceptance of the world has led to a much more effective approach to sustainability and a renewed appreciation and passion for permaculture. I think of it as the shift from sensitivity to integration: from the heartfelt despair, anxiety and sometimes anger inherent in environmental awareness to a more full appreciation and confidence in the holistic intelligence at work in our evolving universe and the ways we can work through this towards real and sustainable futures. The rest of this article is spent on an exploration of this shift and the nature of what I term an Integral approach. This approach is largely based on the work of American philosopher Ken Wilber.

Making the shift allowed me to see that much of my past activity was driven by anxiety and despair, an unrealistic approach to changing the world, and a kind of guilt born of participating in what I thought of as a destructive society. My growing sensitivity generated a lot of turmoil and energy. It was like a rising storm, and I realise now that I was exposed with little shelter and few beacons to safety. Despite the trials and the dangers, it was an essential process. I think it’s a process many others are going through or will go through: an increasingly common cultural pattern as the sustainability challenges mount. It is worth bringing awareness to this process and to making it safer and easier for others to negotiate. From where I stand now, this aspect of people care is every bit as essential as growing food, designing properties and re-localising economies.

Tagari Farm

When I arrived in north Queensland Australia, I found a copy of the Permaculture Designers Manual by this fellow Bill Mollison on my father’s bookshelf. It was fascinating. I was interested in design as I’d studied architecture after my undergraduate degree in literature, but the conventional design disciplines paled in comparison to sustainable design using wind and water, earth, plants and animals. I found a weekend introductory course and shortly after that I drove down the east coast of Australia to Tyalgum in northern New South Wales for my foundation ten-day Permaculture Design Certificate course at the Permaculture Institute with Bill Mollison himself.

At Tagari Farm Bill indoctrinated some 50 of us into permaculture through a ten day process of story, vision, knowledge and ecological understanding, passion, humour and genius that I’ve never encountered since. Not only that, but the amazing people I met on the PDC inspired me and made me feel like I’d found my community and my life’s work. I was hooked. The day on patterns in particular gripped me in a way that I couldn’t quite describe. I was going to be a permaculturist. A few months later I arrived back at the Permaculture Institute determined to take up a licence to do a sustainable forestry project as a participant in what was loosely described as the Tagari share farm.

Tagari Farm was an interesting and exciting place. Bill would draw amazing folks from all over the world. Waves of permaculture design course participants would wash in and out, and over time a small group of people assembled to take up licences on the share farm. I say assembled, because beyond an explanation of the share farm concept in the course or the occasional loose invitation, there was very little supporting structure for actually joining the share farm or getting a licence. One simply had to make one’s way as best one could. Despite the obstacles and lack of support, the group that was to form our period of experimentation at the Permaculture Institute’s Tagari Farm, took shape. Up to a dozen of us were developing projects in market gardening, tropical fruits, fowls, rabbits, aquaculture, earth works, permaculture training, design, forestry, tree crops, bamboo, tours, education and publishing.

The Tyranny of Structurelessness

In retrospect, this experiment couldn’t have ended in anything but failure. Although most of us lived nearby, off the farm, the social dimension to our lives there was intense and our project coordination dysfunctional. There was an implied understanding that all we needed to make permaculture work was our shared ethics, principles, practices and a rugged commitment to earth care. This belief was held up as an almost magical elixir for organizational development. This strategy proved woefully inadequate and things degenerated badly over time. Attempts by some of us to organize ourselves and to create some structures and processes were not supported. We suffered from the ‘tyranny of structurelessness’: a rejection of all structure in social affairs because the existing structures in our society were seen to be controlling and destructive.

I can remember one quite funny, but at the time quite terrifying, episode where a few of us gathered around Bill’s kitchen table to put forward a proposal from some of the share farm licensees. A dark look crept over his face as he read it, and with the full force of his personality (which for anyone who has felt it, will, I think, be counted as one of their more memorable experiences), proceeded to challenge our initiative as an attempt to take over the functions of the Permaculture Institute. Function, or a lack of it, was exactly why we were there, but there was obviously no arguing the point, so we retracted the submission, opened a bottle of port and listen to Bill tell us stories until late into the night.

I have observed similar struggles with structurelessness in many environmental projects and sustainability experiments over the ensuing years. Inevitably the lack of effective organization leads to breakdown in the group and ends in chronic dysfunction or complete failure. I liken this to trying to operate your body without any bones. The end of our few years at the Permaculture Institute was punctuated by the tragic suicide of one of our number. Almost all of us left shortly after that devastating event. Previous and subsequent groups suffered more of less the same fate. What was Tagari Farm now stands overgrown, empty and abandoned to this day. In my view, all the good effort and resources put into earth care were largely undone by a failure of people care. A project meant to be a leading example of permaculture practice suffered the ignominy and irony of being unsustainable by virtue of not developing its own stated second ethic.

The Burn-Out Mill

Thus began my process of facing up to the unhelpful myths and dogmas of permaculture. Rather than rejecting permaculture outright or, alternatively, hiding these truths, I wanted to explore what it would take to get permaculture theory to translate into effective practice at the community level. Could it be used to demonstrate a sustainable way of living? Was it possible for the theory to translate into reality? Could the claims, especially the more grandiose claims made by some in permaculture, be supported? Could we live up to these expectations? Could it be used to transform our society in practical and enduring ways? Were we fooling ourselves?

I think it is fair to say that our critics have keyed in on this lack of effective practical demonstration: initial enthusiasm and over-exposure all too often giving way to unsustainable outcomes. Despite the large number of permaculture adherents, in the wealthy Western countries at least, where permaculture is the designated sustainability strategy, successful practical demonstrations beyond the level of the family property are relatively rare. The ones that do persist are often short lived, sometimes only cosmetic variations on mainstream living, or obviously unsustainable. Many entering permaculture are underwhelmed when they go looking for the examples to meet their expectations. Then there is the grim battle in chronic dysfunction to make permaculture projects work though unsustainable means. This is another unfortunate pattern in environmental and sustainability work in general and permacultue in particular. I call it the ‘burn out mill’. Whether we acknowledge it or not, we are famous for it: individuals burning out to prop up something that just isn’t sustainable in-and-of-itself. Or, using wave after wave of people recently indoctrinated, motivated more often by despair than by hope, to work in permaculture projects where their energy is consumed and their expectations go unmet. These people then either return to conventional life or, ignoring a dissonance between theory and practice, perpetuate the myths in their own permaculture work.

I’m pointing out these negative aspects of permaculture, not because I think all permaculturists practice them, or that initially they can entirely be avoided, but because they are elements of our discipline that lack integrity. We should acknowledge them and reform them if we are to make a more effective contribution to sustainable transition. The end cannot justify the means. We cannot, on an ongoing basis, demonstrate sustainability in unsustainable ways, interpret this as success and expect to be taken seriously. Here, I do need to pay tribute to those practitioners who do have the enduring functional examples and to acknowledge all their hard work and commitment to getting it right.

Permaforest

In spite of my experiences at Tagari Farm, or perhaps because of them, I embarked on a permaculture project to integrate earth care more fully with people care and to try and resolve some of the other challenges I had encountered in my early attempts at practicing permaculture. In an initial partnership with another Tagari participant, Gary Cowan, we located a suitable property. The sustainable forestry enterprise started at Tagari Farm became a successful little tree planting and reforestation contracting company. In short order I re-formed it into Permaforest Trading Trust which funded its slightly younger twin, a charitable sustainability education organization called Permaforest Trust. This dual trust structure, a trading trust and a charitable trust, is straight out of Chapter 14 of the Designers Manual. Bill Mollison gave me a copy of the Permaculture Institute’s trust deed to use as the basis for Permaforest Trust’s deed. I am the Trustee of both trusts and manage them by their deeds, which mandate trading and sustainability education respectively. My tree planting contracting business grew and funded the Permaforest Trust. It became the owner of the 170 acres of undeveloped farm land and forest we had located. The land was at Barkers Vale in NSW, half an hour west of Wollumbin (Mt Warning), on the lush and rugged sub tropical volcanic back slopes of the old shield volcano’s caldera.

In 1998 Permaforest Trust began to use the funds gifted to it by Permaforest Trading Trust to establish a permaculture education centre and demonstration farm on the land. This centre was referred to as Permaforest Trust. The idea was to create an educational community- a residential centre where people could live together temporarily and learn permaculture through modelling sustainable rural living. At first the number of participants was quite small but as we built the accommodation and common areas and planted gardens and trees, the numbers grew. Eventually we built up to an average population of about 20 students, managers and visitors living and working at the centre. After much hard work and persistence, based in large part on an Integral perspective, we managed to create a stable and functional centre where we demonstrated a reasonable attempt at permaculture community living. Our resource use was much lower than most Australians, our permaculture practices were moderately productive and were having a beneficial effect on the land. In the end, I think, it was actually much better than that, and we did manage to achieve something quite special and unique in the way we practiced permaculture, particularly with regard to people care and the community dimension.

There were two reasons why we ended the experiment at this point. Firstly, after a period it was very difficult to improve sustainability indicators. We were remaining dependent on the goods and services of a consumptive and energy-rich economy. Secondly, the energy and resources required to facilitate the human dimensions of the project made it unsustainable for those of us managing it. My experience is that this is something of a pattern, and as such I couldn’t see that it was a recommendable strategy to scale up. In its own way it was another unsustainable attempt at modelling sustainability. This is not necessarily a bad thing if recognized, and it may be that this paradox holds an important clue for developing more effective perspectives on sustainability into the future. That is, it may be more effective to look at sustainability as a process rather than a destination: an ever-receding goal at the edge of endeavour.

The period of experimentation with the educational community at Permaforest Farm lasted roughly a decade – from 1997 to 2007. Initially it was my home and that of a few other committed participants, but as the numbers grew and the centre took shape, so did the challenges. Earth care, in all its various manifestations – gardening, other elements of permaculture design, organic agriculture, sustainable forestry and bush regeneration primarily, while not without problems, was not our main challenge. The recurring limitations to learning and living permaculture were the people. While I tried to put a special emphasis on people care strategies based on my experience at Tagari farm, I still managed to seriously underestimate the magnitude of this challenge. It wasn’t until I developed a more Integral approach using strategies for the ‘inner landscapes’ of self and culture to the same degree that my permaculture training had taught me to focus on strategies and techniques for the ‘outer landscape’ of nature, that we really started to make progress.

An Integral Approach

If I had not come across the Integral framework created by Ken Wilber, it is unlikely that the Permaforest project would have reached such a satisfying conclusion. Wilber’s work helped me understand a whole range of challenges in my permaculture work from a new perspective and to solve them in novel and effective ways. Before we can move on to the practical examples of how an Integral orientation helped us meet the challenges at Permaforest Trust, we’ll have to spend some time on a thumbnail sketch of some relevant aspects of Integral Theory. I realize that a brief treatment of some seemingly academic aspects of integral theory may initially seem overly technical and unnecessarily abstract, but I would ask the reader to persevere. Alternatively, you may skip to the summary at the end of this section, or read it knowing that initially a comprehensive understanding is not necessary. I’m including it here because I think some readers will want a basic understanding in assessing its usefulness. While the theory may appear quite abstract initially, it becomes much more concrete as it is unpacked and related to practical situations. I’m outlining the framework here as a very effective practical tool. The interested reader may wish to consult some of Wilber’s works cited in the reference section.

David Holmgren, co-founder of the permaculture concept, mentions in his writings that permaculture is part of the postmodern cultural emergence. With its foundation in the new, more holistic systems sciences, including ecology and systems ecology, its counter culture adherents, radical self-reliance, questioning of industrial institutions and processes – especially green revolution agriculture- as well as its sensitive ethics, permaculture can be counted as one of the most influential grass roots initiatives of this period. The modern industrial era started to emerge some 400 years before the postmodern, the traditional agricultural period had its beginnings up to 10 000 years before that, while the original period of human history had its beginnings some hundreds of thousands of years before that, indicating that the pace of cultural development is speeding up over time.

Only 40 years into the postmodern period, it is thought by some that the post-postmodern, or ‘integral’ era is now emerging. Among many other things, postmodern culture can be credited with sensitising us to the diversity of natural elements, their interconnectedness and our own dependence on these life systems, but like the material gains of the economic industrialism of the modern period before it, this ecological and social sensitivity is limited in its capacity for sustaining the human project. At this time in history, personal, cultural, ecological and social dynamics are accelerating and new challenges requiring new ways of looking at the world are already upon us.

The Pattern That Connects

Integral Theory, because it is a philosophy that can include a place for everything, and because it is comprehensive enough to entirely reject nothing, is often referred to as ‘the pattern that connects’, giving it a strong association to permaculture through its own relationship with pattern understanding. A postmodern view sensitises us to the interconnected diversity of elements in the natural world, but it is an integral orientation that is critical for identifying the patterns that shape these parts into coherent designs, again demonstrating a resonance with permaculture as a design discipline. Permaculture aspires to a more Integral approach through the recognition that sustainability practice must contain ethics as well as design techniques. That is, it must work with values which reside in the inner landscapes of human experience as well as the material outer landscapes of natural ecologies and human economies. Despite these similarities, permaculture has not yet emerged as a fully Integral discipline. I think the aspects of Integral Theory outlined below can contribute to a more fully integral permaculture and that this is an interesting, and in my case, very helpful direction to head with the practice of sustainability.

Holons

One important aspect of Integral Theory is the widely held systemic or ‘design thinking’ understanding that everything is both a part and a whole at the same time, or a ‘holon’. Whole atoms are parts of whole molecules, which are parts of whole cells, which are in turn parts of whole organs, which are parts of whole organisms in the ongoing structuring of more complex forms. This view of nature as a kind of nested hierarchy or ‘holarcy’ is now common in the ecological and systems sciences, contributing an essential understanding to general eco-literacy.

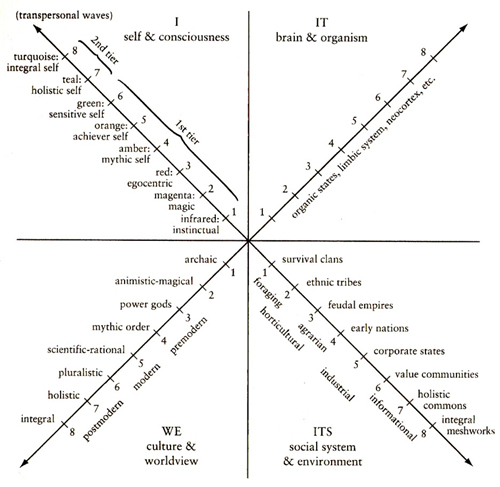

Here, Integral Theory adds the view that just as partness and wholeness are limited perspectives on one integrated part/whole, so too is its status as either a material object or an aware subject. In fact, any holon is an integrated occurrence with four main aspects or perspectives: partness (individual), wholeness (collective), objectiveness (exterior) and subjectiveness (interior). (See Figure 1).

Different cultures hold views that reality is either inner experience or outer objects, fundamentally material or ultimately spiritual; basically just matter or essentially mind. The integral view is that it is both, and that combined with the view that things are also parts and wholes these four aspects are just different perspectives on one thing. These four aspects are often referred to as the four quadrants of a holon. Add to the concept of the four-quadrant holon the idea that more complex forms evolve in a dynamic fashion through the integration of less complex forms and we have the bones of an integral view: parts and wholes; insides and outsides; developmental evolution.

I-Space

If we look at the intersection of the interior perspective (subjective inner aspect) and the individual perspective (part aspect) of a person we could call this the ‘self’- one’s own subjective experience or awareness, and all of the related thoughts, emotions and sensations that manifest there. In permaculture there is a nascent recognition of this perspective as Zone 00.

We-Space

If we look at the interior perspective (subjective inner aspect) of the collective perspective (whole or community aspect) we get ‘culture’- a group’s shared interiorities like ethics and values. In permaculture this perspective is honoured through the ethics of ‘earth care’, ‘people care’ and ‘fair share’.

Eco-Space

Where we look at the exterior perspective (objective outer aspect) of the individual perspective (part aspect) we get a view of the characteristics and behaviours of that individual element of nature; where we look at the exterior perspective (objective outer aspect) of the collective perspective (whole or community aspect) we get a natural systems perspective represented by both ecologies and economies. In permaculture this perspective is honoured through the principles and practices of sustainable design in agriculture and the built environment.

For the purposes of this discussion we can place both quadrants in the right hand half under the name ‘nature’ (see Figure 1). Self, culture and nature are called the ‘Big Three’ in Integral Theory. In my permaculture work I often refer to them as ‘I-space’, ‘we-space’ and ‘eco-space’. These are the three major domains of human experience and therefore it is essential to include each of these perspectives in any initiative. Just this one seemingly simple realization provided essential and powerful strategies for some of the most serious challenges we faced at Permaforest Trust, as we will see.

Figure 1. The four quadrants of a holon. After Wilber

Body, Mind and Spirit

The evolutionary aspect of Integral Theory translates into the view that everything develops in stages, and that each new stage both transcends (goes beyond) and includes (is actually built from) the elements of the level before. Permaculture tells us that careful observation of any natural process will reveal a pulsing dynamic of identifiable stages of development, whether in the growth of a plant, the implementation of a design or the succession of an ecological system. For instance, we can identify the ecological succession of a forest ecology from pioneer stage, to early secondary, late secondary and finally to the mature stage. What is important here is that it is impossible to exclude or reject anything from the previous levels of development without destroying the whole. The whole is made up of all previous stages. Pioneer species are embodied in the soil fertility of the later stages. It would be impossible to skip this stage or to remove it from the process. The trick is to understand how pioneering processes work and when and how to use them. In permaculture for instance, we use the principle of accelerating succession through the pioneer stage or alternatively maintaining a system in its productive pioneering phase. The idea is to work with pioneer dynamics and to make the pioneer stage as functional as possible in service of the whole process. This understanding of stages is a core eco-literacy in permaculture, but in Integral work the principle is used more widely; this evolutionary dynamic is translated from eco-space into we-space and I-space.

If we take the evolutionary unfolding from a big picture perspective, it can look something like this: where conditions in the realm of matter (the physiosphere) are favourable, life can arise; where conditions are favourable in the realm of life (the biosphere) mind can arise; where conditions are favourable in the domain of mind (the noosphere) then spirit can arise (the theosphere). In short, the process of evolution goes from matter to body to mind to spirit. If this is true, then we have a way to integrate the material worldview of the modern west with the more spiritual world views held historically in the east. Mind and matter are not opposites, but two aspects of one evolutionary continuum.

If we step away from the big picture and look at an individual human being, we can look at the evidence that people go through a process of growth and development. Stages of personal development have been identified by a number of researchers including Abraham Maslow, Robert Kegan, Jean Piaget, Susan Cook-Greuter and Jane Loevinger to name just a few. They may be looking at different aspects of development and have different names for their stages, but the one commonality is that they have all identified a process of growth much like the general one outlined above, where each new stage transcends but also includes the previous stages. The simplest set of personal development stages is from body (emotion centred awareness) to mind (mental/rational centred awareness) to spirit (more compassionate transpersonal awareness). Understanding this progress in human development helps us understand the importance of integrating the wisdom of the body with the intellect of the mind in order to gain a wider, transpersonal level of awareness that can support a more integrated, dynamic view of reality.

Altitude

Similarly, theorists such as Jean Gebser, Clare Graves and Don Beck have identified stages of development in culture. At this point I’m going to simplify and generalize this work for the permaculture context based on my own experience. For practical purposes we will discuss four cultural stages. I’ll name them using the colour scheme from the Integral framework referred to as stages or levels of ‘altitude’. Altitude is a general marker of development that may be used for correlative levels in culture (collective) and the self (individual). See Figure 2 for a diagram of correlates in each quadrant. Each cultural level or altitude is characterized by a core set of values and by an increasing capacity for inclusion. Values are simply what the people at this stage of development collectively hold to be most important; inclusion is the capacity to include others in one’s sphere of care. Each level of altitude also leads to definitive worldviews that shape how its members see the world. Most people can intuitively sense levels of cultural development if they are presented using some commonly recognizable traits, which is how I’ll introduce them here. Altitude, as mentioned above, also functions as short hand for levels of individual development. I will attempt to introduce cultural and personal levels of altitude concurrently below.

Amber

Amber cultural groups value belonging through order. They are often absolutist and patriarchal, with strong hierarchical social structures. Individuals expressing amber altitude will have strong community and family values and mythic religious beliefs. This value set is often expressed politically through groups promoting family values and traditional morals. Older children who have mastered and enforce household or community structures are expressing an amber orientation. Amber cultures transcend earlier cultures and can be seen as an evolutionary step that allowed for their aggregation in the development of complex civilizations in the agricultural period. The sphere of care is wider than anything that came before, but still limited to a nation, club, team or other identifiable group thought of as ‘my people’. I’ll use the term ‘traditional’ when referring to communities and individuals oriented around this level or stage. The members of this level of altitude amount to about 25 percent of the Western world. Amber worldviews started to emerged as long as 10 000 years ago.

Orange

At the Orange level of altitude people value individual rights, achievement and performance. Economic material gain is often identified as the way to generate the greatest good. Rational, scientific understandings of the world are most highly regarded. Orange typically emerges for the individual around late high school or early adulthood. Orange cultures transcend Amber cultures in that their wider ethics of productive economy create a market that can include more people within their system of organization. Orange is seen as the worldview of the enlightenment and the subsequent period of rapid industrialization. I use the term ‘modern’ when referring to this level of altitude. The members of this level of altitude amount to approximately 40 percent of the Western world. Orange perspectives started to emerge en mass about 400 years ago.

Green

Green values sensitivity and diversity. It can include multiple perspectives on reality. People in Green are often sensitive to social injustice, animal rights and ecological destruction. Their sensitivity makes them good communicators and their values are often expressed in postmodern academic concepts such as the deconstruction of power, relativism and contextual approaches to knowledge and understanding. Green’s sphere of care is wider than Orange’s in that it can care for all people regardless of whether they are customers or trading partners. It is fully world-centric in orientation and will manifest as lifestyle choices like vegetarianism as a response to the imperative to care for animals. Green sensitivities inform postmodern perspectives from environmentalism and deep ecology, fair trade and anti-globalization activism, to collaborative online communities and the design of advanced communications architectures like the world wide web. Green altitude fosters the worldview that I refer to as ‘postmodern’. The members of this level of altitude currently represent about 20-25 percent of the population of the Western world. Green, postmodern perspectives emerged as a general world view only some 40 years ago

Teal

While all the altitudes so far represent a developmental advance (and of course inclusion) on the level before them, at the Integral level of altitude there is a major change in the nature of development. The altitudes from before traditional to postmodern are all exclusive worldviews. That is, if you ask, say, a modern executive of an export wood chipping company at Orange attitude if they think that a post modern Green initiative to save the forest is responsible, they will say no it is not. Alternatively Green activists will not condone wood chipping as responsible. A traditional farmer or original inhabitant will have their own different interpretation of the common good in this instance. In fact none of the first tier altitudes related here will accept the values of the others as fundamentally legitimate.

At the integralTeal level of altitude the entire holarchy of nested development – from before traditional to traditional (which transcends but includes worldviews before it) to modern (which transcends but includes the previous two) to postmodern (which transcends but includes the previous three) – is seen as an integrated whole. From an integral perspective, you can’t remove modern values of productivity and exchange from society any more than you could remove your lungs or your kidneys from your body. At an integral altitude, all worldviews are accepted as valid. The way forward is not to pick one at the exclusion of the others, but to integrate and balance the different ways of seeing the world for the best overall outcome. The way to work with this practically is to encourage healthy and appropriate expressions of each world view where they are found. Like a Green postmodern approach, a Teal integral perspective accepts diversity, but it goes farther and recognizes patterns and order in diversity necessary for unitive health. By virtue of its pattern oriented, more comprehensive view, an integral perspective can generate an inclusive, compassionate capacity for all previous altitudes, marking it as a second tier altitude. Because of their more exclusive nature, the altitudes Amber, Orange and Green are referred to as first tier altitudes. Members of a second tier, integral altitude represent roughly 2-3 percent of the Western world, with some evidence of a more substantial demographic trend in this direction. An integral world view is only now emerging as a widespread set of perspectives in the Western world.

In summary we now have the three domains of Self/I-space, Culture/we-spaceand Nature/eco-space (based on the quadrants) as well as four levels: Amber/traditional, Orange/modern, Green/postmodern and Teal/integral (based on altitudes) to work with as we explore an integral permaculture. Technically the foundation Integral framework developed by Ken Wilber contains five elements: quadrants and levels, which we have covered here, and states, lines and types, which we do not have time for in this short chapter. The interested reader should see A Theory of Everything by Ken Wilber for a more comprehensive introduction.

Figure 2, from Wilber Quadrant diagram showing levels

An Integral Permaculture

Now that we have a background in some of the basic elements of integral theory we can take a brief tour through some of the ways that it assisted our permaculture practice at Permaforest Trust. It is fair to say that as the project grew in scope and in numbers so did the challenges. For a while they seemed insurmountable and there was a great deal of confusion as to why our permaculture ideals and practices were leading to such dysfunctional outcomes. One by one though, we put in place strategies based on a more integral perspective that lead to real results and tangible improvements.

We-Space Strategies

One of our first realizations was that we really only considered it permaculture if it was earth care. Our attention was almost exclusively focused on creating outcomes in eco-space. Care of people, we-space, was almost always seen as something secondary. I don’t think we were unique in this. It is not at all common in my experience to find permaculture projects that explicitly put people first. Although people care is the stated second ethic of permaculture, and even though we were initially conscious of the importance of the community dimension to our project, initially anyway, it always came second. It was only after realizing that it needed to be at least equal to eco-space practices that we started to see improvements. After this realization we developed a detailed community handbook that spelled out our values and expectations. We sent it to people before they came and asked them to voluntarily commit to the system. We put in place management and support team systems to encourage adherence to the community system and we scaled back on eco-space activity to support more we-space activity.

I-Space Strategies

A natural follow on from re-prioritizing we-space, was the realization that individuals needed significant support as well. Initially most of us managing and participating in the project were firmly rooted in a sensitive, post modern/green worldview. This has common challenges like ‘endless meetings’ where consensual decision making included much discussion and dialogue about feelings and interpersonal dynamics. But it also had more serious dimensions. The realities of restrictions on personal freedom inherent in community living often caused ongoing psychological and emotional trauma, even among the most well-meaning and passionate of participants.

Personal freedom is a hidden form of wealth or resource use in postmodern culture. Only very wealthy industrially based societies like our own can support so many people with so much autonomy. When it is taken away or, in our case, voluntarily given up, even by people with strong ideals of low resource, community living, it can cause significant resentment, rebellion, anger and depression. Putting in place strategies to support the healthy transition to a more ecologically sustainable lifestyle was the most taxing of all the dynamics we had to deal with. We did manage to develop strategies for managing and supporting these personal transitions, but in the end, given our isolated rural setting and minimal resources, we could not sustain this effort. Management was constantly in danger of burning out through using their own energy and personal resources to support the participants’ I-space challenges. It is essentially why we ended our experiment of modelling a rural permaculture educational community. To this day, I see I-space challenges as one of the most significant aspect of transitioning to a sustainable future.

At this juncture it may look like an Integral perspective was not enough, but I look at it somewhat differently. Firstly, while an Integral approach has proved very effective, it is not a cure all. And, secondly, if we didn’t develop an awareness of the importance of I-space, we might have burned out before we could successfully conclude that phase of the work of Permaforest Trust and move on to more viable undertakings. An Integral perspective was critical in avoiding collapse by allowing us to see our limits in the I-space dimension. In a more general sense this may be a very important Integral perspective on the dynamics of global sustainability transition. Trauma and healing modalities as well as personal growth and development practices may become some of our most powerful practical strategies in sustainability.

The Tyranny of Structurelessness- Using Healthy Amber

Another aspect of the project’s participants being generally oriented in a Green/postmodern worldview was an overt regard for non-hierarchical social structures. This extended to a disregard and a general dislike and distrust of structured social arrangements in general. This is an understandable reaction to the oppressive dominator hierarchies at work in modern society. They are rightly seen as unhealthy and unsustainable in their pathological form, but removing all structure as a reaction can lead to equally poor outcomes that become a tyranny in themselves – a ‘tyranny of structurelessness’. I’ve already related the dysfunction caused by a lack of structure at Tagari Farm. Similarly, for us this structurelessness lead to a confusing morass of unfinished tasks, unmet commitments, interpersonal dysfunction and personal dissatisfaction. A postmodern view allowed us to deconstruct unhealthy power structures, which is fine, but it didn’t help us focus on how to put the parts back together in a functional way. At times it felt like we were compulsive deconstructors adrift in a decaying marsh of our own undifferentiated deconstructions. The solution provided by an Integral perspective was to get in touch with healthy Amber values of clear structure and organization in social relationships.

Having a community system and a handbook to support it, mentioned above, was helpful, but what really made it work was explaining it and practicing it in an acceptable way. We carefully and intentionally related that it was essential for the health of the community that people meet their community commitments, and that it was essentially unethical in a fair and equitable community system to let others down. Ultimately, and this was the hardest part, we had to enforce this structure. We had a procedure of positive support and motivation for people who struggled, but there was a limit after which people were asked to leave if they could not meet their commitments. There was no negativity attached to this, only a recognition that the situation need to be resolved for the wider good. This may have been our most successful integral intervention: things became substantially better after we established and enforced this community structure – it was like night and day. The level of functionality and the general well being it facilitated was, in my view, the reason visitors often commented that they felt there was something special going on at Permaforest Trust.

Poverty Consciousness- Using Healthy Orange

Another important dynamic having a negative effect on the project was a general ‘poverty consciousness’. What I mean by this is that there was a general disdain for anything to do with money and commerce- poverty was seen as a kind of sustainability virtue. Often people wore a kind of faux Western poverty as a badge of honour. This seems to be endemic in the environmental line of development in postmodern circles, which I refer to as ‘Deep Green’. I use this term in much the same way it is used in Deep Ecology: to denote a more meaningful depth of engagement in the topic. Other lines of postmodern development like internet technology, environmental policy making and the emerging green public relations field, seem to have less aversion to money, but it can be seen in others like social activism, fair trade, green politics and aid and development circles. In my view, this is another reaction to over-consumptive industrial economic processes that are seen to be so environmentally destructive. Again, it is understandable, but there is actually nothing healthy about writing off productive economic patterns and commerce. We didn’t focus on the business of environmental education as much as we should have in the beginning and it caused a lot of stress. There was, I have to say, an entitlement mentality when it came to education. This extended to us even though we were an independently funded, self-reliant, pioneering educational facility with few resources relative to government or corporate education programs. We were trying to model self-reliance and did not have any direct government support.

The answer to our economic stress was to get in touch with healthy Orange values of productive exchange and economy. We put together a business plan, budgeted effectively, marketed our product, made our fees clear, collected them and developed good value in our educational offering. We actually had good business skills, but we needed an Integral framework to put us in touch with the importance of integrating them fully into the project. We also extended this ethic of productivity to our permaculture work and it helped us to hit new highs in organic food production and sales. As with introducing Amber inspired social structures, putting in place Orange structures around commercial processes and productivity systems led to some very subtle but definite peer pressure to diminish these activities. They just looked too ‘conventional’ and therefore unsustainable to anyone viewing from a first-tier perspective. Over time we learned to stand firmly in an Integral perspective, and as we did, more and more participants started to see the benefits and to investigate an Integral perspective for themselves.

The Heart Circle – Using Healthy Green

At this stage we were well aware that although we had manifestations of some unhealthy Green patterns, we did not want to give away Green perspectives altogether. After one gains some perspective on Green values and patterns there can be a bit of a tendency to develop an allergy to them and to the Green level of altitude in general. This is typical of first tier development. When one develops to the next perspective it is inhabited exclusively, with little room for previous values or views. It is a bit like the pattern of reformed smokers who becomes extremely critical of their friends who continue to smoke.

We became conscious of nurturing our Green strengths, diminishing the pathologies and integrating with values and practices native to other altitudes. Practicing sustainability became a bit like practicing Traditional Chinese Medicine – we worked to balance and integrate all of the energies and dynamics of our system for enduring health.

One of the most important Green processes we developed was the Heart Circle. This is a process modified from Rainbow Gatherings. All participants sit in a circle and take turns speaking. One person talks at a time only, and everyone listens until they are done. It is a sacred, intentional space where people can speak their truth and speak from the heart. Commentary can be extremely personal and deeply critical. It is a very powerful and intense interpersonal space, full of emotional depth, deep honesty, sensitivity, great joy and equally great sorrow, anger and sometimes immense ecstasy. By developing this space and intentionally containing this energy we could honour the depth and beauty of being Green in a healthy way that allowed us to integrate it into our lives without this powerful energy dominating all of our other process.

Conclusion

I would like to emphasize here that the integral framework is a map only, and a simple one at that. Reality, the territory it tries to describe, is infinitely complex, ultimately mysterious and if we are honest only partially knowable. A good map, though, can be very helpful in navigating a real terrain.

Using even the few insights from a basic Integral perspective related here was enormously helpful in our work during the ten years Permaforest Trust experimented as a rural permaculture educational community. The Integral framework continues to inform my understanding and work within permaculture, Permaforest Trust and sustainability more generally. There was a time when the pathologies, dogmas and difficulties of ‘making permaculture work’ in a Green milieu almost caused me to give it away altogether. Now, I can see the strengths of permaculture more clearly and I am more effective at working through its weaknesses.

An integral perspective allows me to see my world in a similar way. I am comfortable with it again. Not through ignorance, but through understanding. It doesn’t have to be rejected, I don’t have to live outside of it to have an ethical existence, it doesn’t have to fought, it is not going to fall in a screaming heap and I don’t have to fix it. It is beautiful because it is what it is and it cannot be anything other. Its current dynamics are obviously unsustainable, but I now have a faith in the patterns of systemic adaptation, organization and change. There is a Source of order and evolution at work in our world and there is great power in working with this process. This is not a naive or passive faith. It is, indeed, a clear awareness, a critical call to action, but it is not by fighting the various parts of our greater Self that we will persevere. Our greatest hope lies with the compassion to harmonize the great depth and span of reality using the principles and patterns of Natural organization.

An integral permaculture must use its strength for identifying natural patterns and principles in the ‘environment’ and apply them to the ‘environments’ of self and culture as well as nature. We must use our insights more comprehensively by recognizing and integrating the many worldviews held by the planet’s many peoples. And, we must have the compassion to embrace all of our world, while having the wisdom to eliminate pathologies wherever we find them. While an Integral permaculture may not be about Spirit, it does make room for genuine spiritual practice, allowing the integration of this very important and powerful aspect of human and cultural development. Becoming skilful in combining these elements is a great step forward in facilitating the enduring health of our civilization.

Few disciplines have permaculture’s practical foundation in learning and using natural patterns and principles- fewer still have integrated foundations in the ethics of people care and earth care. Also, permaculture has a unique capacity for facilitating local community self reliance in food, energy and other critical commodities during sustained periods of resource decline. If our perspective about approaching bio-physical limits to growth and impending energy descent is correct, then a more fully integral permaculture- one that can combine the strengths of the various sectors of our communities, support individuals in personal transition and offer viable alternatives in agriculture and local economy- will become critically important. In a future of declining outer material growth there is an opportunity and a likelihood of an increasing alternative trend towards inner, personal and spiritual growth. An Integral permaculture can become a vehicle where providing us with what we need becomes a way of realizing the potential for who we can more fully become.

References

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality: A startling new role for religion in the modern and postmodern world. Boston: Integral Books.

Wilber, K. (2001). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science and spirituality. Boston: Shambhala.

Hi my loved one! I wish to say that this post is amazing,

great written and include almost all significant infos. I’d like to see

more posts like this .

Hi Tim,

I’m a practising permaculturalist (ie. designing and implementing on my own land) as well as an engineer. I *like* patterns and systemic thinking. Yet, when reading about Integral Theory or PatternDynamics, I’m always stuck with this question in my head: Yes, but what’s it *for*?

Thanks for continuing to contribute to the community and movement. Please emphasise some practical applications in your articles. What would you have done before you understood patterns, vs. what did you do *because* you understood patterns?

Hi gbell12

Thanks for the feedback and you question. Practical application of theory, or ‘praxis’, is the most important part for me. I have done some online presentations demonstrating the use of PatternDynamics in practical sustainability design projects. I will post them as I get permission to publish them. Currently they are all held by other parties and I’ll need to negotiate to post them. Also, I’ll be blogging and video blogging regularly on the PatternDynamics web site (www.patterndynamics.com.au), showing practical examples of how to use PD. Stay posted!

Best,

Tim

Blessings Tim, thank you for creating applications for integral theory. I have studied the theory for a number of years and am now getting excited about ways to share it in the context of praxis. Looking forward to participating in the evolution of these ideas and practices. Glisten

Hi Jess,thanks for your comment. Glad you like it so far. I’ll be posting a lot more stuff that attempts to unpack Integral Theory-I’m still working through a lot of it myself. Nice to have fellow travelers. Best.

Tim

Hi Tim, thanks so much for your blog. I’m loving it! I’m also a long time lover of ken wilber but sometimes find his writing a little dense.[sleep deprived, baby brain] so i’m really appreciating your unraveling it for me , especially in the context of sustainability and community.

jess